National Endowment for the Arts cuts have big repercussions for Washtenaw County arts

Washtenaw County arts institutions are responding to widespread NEA grant cuts and rescissions this year after President Donald Trump proposed eliminating the agency.

This story is part of a series about arts and culture in Washtenaw County. It is made possible by the Ann Arbor Art Center, the Ann Arbor Summer Festival, Destination Ann Arbor, Larry and Lucie Nisson, and the University Musical Society.

Leaders of the Ypsilanti Youth Orchestra (YYO) were contemplating expansion when they received notice this past spring that a $10,000 National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grant they’d been awarded had been rescinded.

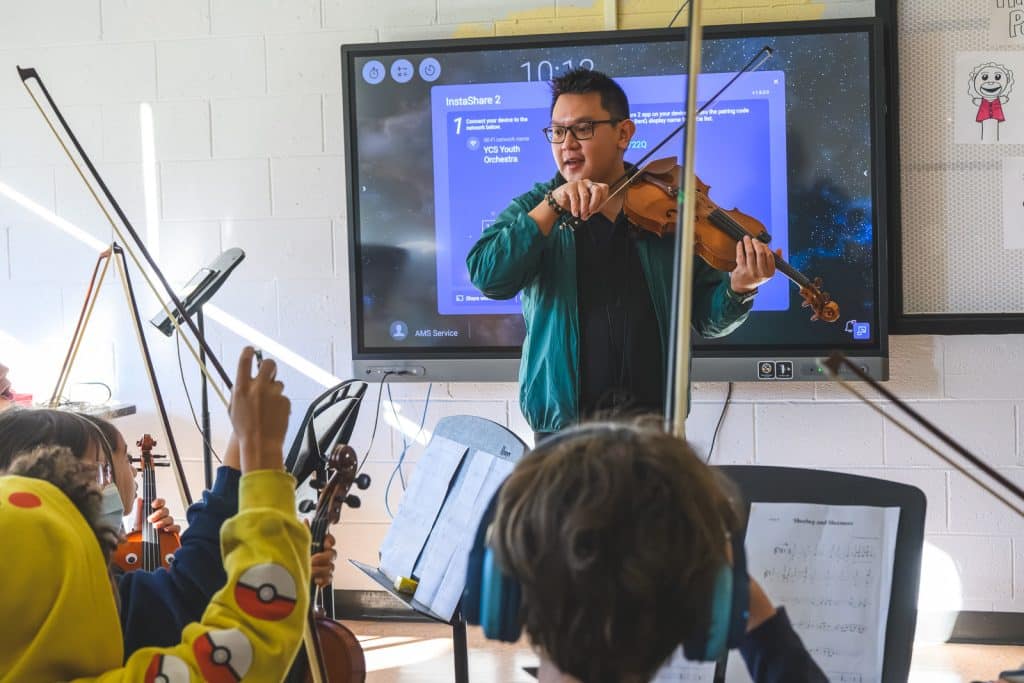

The nonprofit orchestra, founded in 1999, offers tuition-free music education and performance opportunities to more than 200 local students ages 4-18. YYO Board President/Chair Kasia Bielak-Hoops says the organization had just finished “rebuilding” from the COVID-19 pandemic and onboarding a new music director, and staff were preparing for a new period of growth.

“We were ready for it,” she says. “So this [grant loss] just adds a new element. … This year is going to be a ‘let’s see what happens’ year.”

YYO is just one of many Washtenaw County arts institutions that are responding to widespread NEA grant cuts and rescissions this year after President Donald Trump proposed eliminating the agency. The NEA grant cancellation sent YYO in search of alternative funding to fill the gap. For the first time in its history, YYO received financial support from both The Towsley Foundation and the Worthington Family Foundation.

“The goal is that you expand your donor base,” Bielak-Hoops says. “You’re not trying to replace it. … And it’s a relief to have these new funders come in. But it feels like we have to work harder to maintain where we were at. We were naturally expanding, and that enabled us to try looking toward serving more students, with more contact hours. But then we had to re-strategize for this upcoming year.”

Specifically, YYO had to increase class sizes and slightly downsize programming. Bielak-Hoops estimates that 70% of YYO’s budget is covered by grants, while the remaining 30% comes from other sources. Plus, the organization is hampered by its limited visibility. Bielak-Hoops says YYO’s situation is different from that of an organization like Michigan Public, which lost federal funding as a result of the recent shutdown of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

“[Michigan Public has] a … natural audience that they can go and ask, even for small increases, and that can add up to a lot,” Bielak-Hoops says. “We’re surveying families who are in our programs precisely because they can’t afford this type of extracurricular education and support. So, although we can ask, most of the support we get is through volunteers. And even then, not all families are able to do that.”

“It’s this catch-22: if we can’t expand and serve more people, it’s harder for us to be seen in the community, and that’s what attracts [significant] funding.”

The University Musical Society (UMS), a large-scale, world-renowned arts presenter that’s been housed at the University of Michigan since 1880, received a similar spring notice from the NEA that $25,000 in federal funds would be rescinded. However, the three performances tied to the funding had already happened (jazz musician/composer Etienne Charles’ “Earth Tones,” comedian Natalie Palamides’ “Nate: A One Man Show,” and Lebanese musicians Marcel, Ramy, and Sary Khalife’s concert, “Legacy”), leaving the organization with an unexpected shortfall.

According to Lisa Michiko Murray, UMS’ associate director of development, foundation, and government relations, UMS has received annual NEA grants over the past 15 years ranging from $20,000-$40,000. It had most recently received a “recommendation of funding” from the NEA for $25,000.

“In a good year, normally you wait a month for the official approval to happen, and then that’s when the NEA sends out its public announcements,” says Murray, who notes that the NEA generally reimburses an organization after it incurs expenses. “ … When we got an official notice that our recommendation had been withdrawn, I believe it said we no longer met the criteria for funding – which of course had changed since the time we had submitted the proposal.”

UMS appealed the NEA’s decision, but that appeal was denied.

Additionally, UMS had applied for another NEA grant: a creative placemaking program called Our Town.

“We had submitted a proposal two summers ago,” Murray says. “It’s a long wait period with NEA grants, and we didn’t even get to the stage of a funding recommendation, because they just shut the whole program down. Never informed us. We just found out. But that was an even larger grant. We were budgeting anywhere from $50,000 to $75,000 for that grant, and it’s gone.”

At the same time that the NEA began making widespread cuts to grant funding, Republican lawmakers proposed increasing the budget for the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., from $43 million to $257 million. That has NEA applicants crying foul.

“It wasn’t a perfect system, but the NEA was always very thoughtful about trying to be equitable,” Murray says. “That funding went to all 50 states. That pot of money was spread as widely and as equitably as they could, and it’s unfortunate that … a lot of the funding is now being concentrated on these few projects in just one small part of the country.”

You might be confused about what link there is, if any, between federal and state arts grant funding. The NEA has, in the past, provided a certain amount of annual funding to each state’s arts council, for those bodies to disburse as they sees fit. Last year, for instance, the NEA contributed nearly $1 million to the Michigan Arts and Culture Council (MACC), adding to the $10.5 million earmarked for MACC by Michigan’s state budget. (This is why arts organizations that receive MACC grants have also, in the past, been required to include mention of the NEA.)

Though this means the NEA’s contribution to MACC grants generally hovered at only 10%, the state’s per capita arts funding – $0.94 per person for fiscal year 2025 – already ranks Michigan 28th in the country. This year, competition for the state’s only-recently-approved MACC money (a little over $12 million) will be all the more fierce.

Earlier this year, Michigan House Republicans had drawn up a budget plan that eliminated all funding for MACC, and a budget vote planned for July was kicked down the road for months. Finally, though, in early October, a state budget was passed, with MACC funding included.

This was good news. But because of all the political uncertainty, MACC has not yet started to accept grant applications, which has added to the general sense of anxiety around arts funding.

“Normally, you’d submit your application in June or July, and you would find out pretty shortly after [if you got a grant], and then you would get your first disbursement of the grant in October or November,” says Shelby Seeley, producing artistic director and literary manager at Ann Arbor’s Theatre Nova. “ … We kind of had to continue planning a season, expecting not to receive any funding, which was really difficult and scary. It still is.”

“We’re still waiting to hear how this will play out on the ground,” says Lauren London, executive director of Ann Arbor’s Penny Seats Theatre. “ … We know [MACC’s] intent is to have grant applications, but we’re not sure what the timing of those will be, so we’re not 100% sure that we’ll have MACC funding available to art organizations this granting cycle. We hope so.”

Meanwhile, big organizations like UMS, despite suffering sizable federal arts funding losses, are guardedly optimistic about surviving this political storm.

“We are fortunate that, at least in Washtenaw County, we are a larger arts organization with a larger budget,” Murray says. “We’ve definitely felt the impact of the loss of these federal grants, but I think not to the extent that some of our peer organizations did – which just makes sense. If your annual budget is a lot smaller, then losing a $25,000 grant is going to hit harder.”

One need only check in with YYO’s Bielak-Hoops to hear about being at the other end of that spectrum.

“Our bodies are feeling this – our minds and our bodies,” she says. “From shock, and then moving through all the emotions, and then acceptance. … We have to allow ourselves a grieving process, too, for all the things that we used to take for granted and expected and adjust to this new normal. … It’s impacting not just organizations, but people. So everything is slowed down. It feels like we’re walking through mud. So that’s where we’re at. But [YYO’s] program is going. … People are still making it happen. And that we can celebrate.”