Ypsi activists advocate for women’s prison to address mold and related health concerns

Ypsilanti-based advocacy group Survivors Speak and its founder, Trische’ Duckworth, are turning up the heat on legislators, asking them to address life-threatening mold at the Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility in Pittsfield Township.

Ypsilanti-based advocacy group Survivors Speak and its founder, Trische’ Duckworth, are turning up the heat on legislators, asking them to address life-threatening mold at the Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility (WHVCF) in Pittsfield Township.

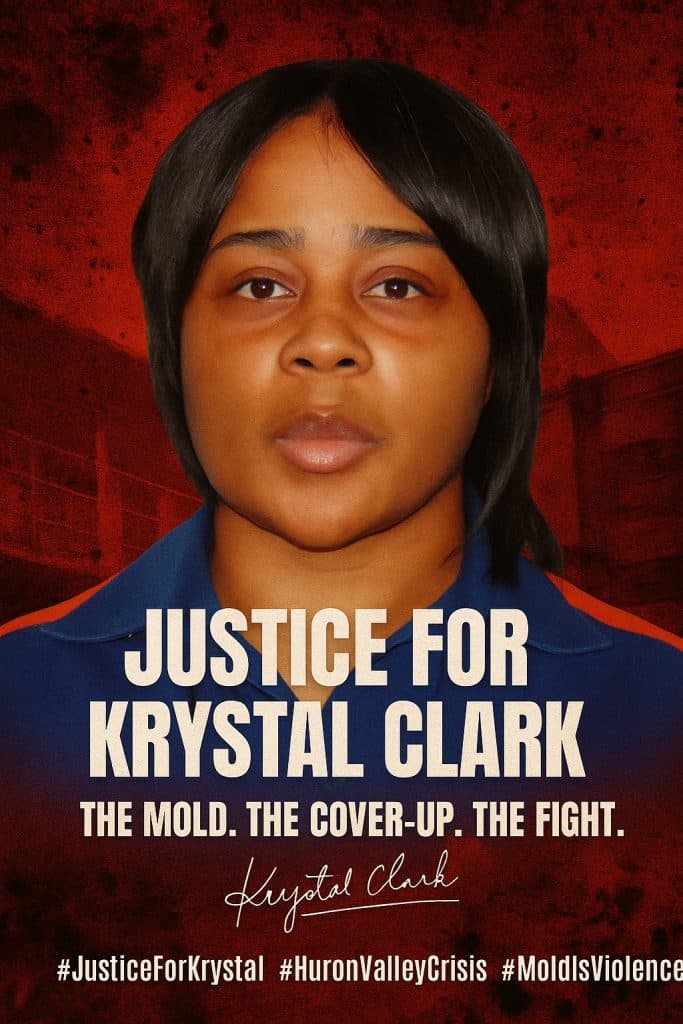

Duckworth says she and other advocates are promoting legislation that would shut down the mold-ridden facility and move the women inside to safety. The effort to address toxic mold in the prison has been going on for more than 10 years. In 2020 Survivors Speak came out as a major voice for Krystal Clark, a WHVCF inmate whose health has deteriorated due to an aspergillus mold infection in her ears and lungs.

Clark has literally become the face of the effort. Her advocates share flyers with before-and-after photos of her, with the “after” shots showing sagging muscles in half her face. Supporters say Clark should receive medical parole because she might die, but she’s not the only one affected.

Other women have come forward to talk to local and state legislators and media outlets about conditions that negatively affect both WHVCF inmates and staff. Mold concerns at the prison go back more than 10 years, and a U.S. district judge ruled in June that the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) was not entitled to immunity from the case. The court found that plaintiffs in the case had provided adequate evidence that conditions in the prison lead to illness and that officials were aware of the problem. But Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel and MDOC officials filed an appeal and a motion to stay proceedings in the case in July.

A group of women who have been affected by mold and poor health care at WHVCF came together Oct. 17 in a Zoom meeting with state and local officials.

Anita Posey, who was incarcerated at WHVCF from 1997 to 2012, says she observed mold in the prison as early as 2005. That means incarcerated women have been bringing those conditions to the warden’s attention for at least 20 years. Posey and all the other women on the Oct. 17 call cited instances of being told to clean up and paint over mold when MDOC expected some kind of inspection.

“They were giving us extra bleach and gloves and a mask, but we didn’t know what we were doing,” Posey says. “That’s supposed to be done by experts that are thoroughly trained and certified.”

Another formerly incarcerated woman, Rebecca Trevino, says she lost her eye due to medical neglect at the women’s prison. She’s eligible for disability but says she’d prefer to work.

“I enjoyed working, and disability doesn’t even cover rent nowadays,” she says. “I was more independent before I got sick. It’s been life-changing.”

Former WHVCF inmate Tracy August says she was there to support the other women with their fight against the mold infestation, but she notes that health care in prison isn’t very good, even beyond the mold issue. Wellpath, the for-profit health care organization that runs the WHVCF infirmary, filed for bankruptcy in November 2024 while facing 1,500 medical malpractice lawsuits. The company emerged from bankruptcy in May.

“These women that are suffering in there with no help, no hope, it’s just inhumane,” August says. “People in third-world countries get better treatment. These people have families. They’re coming back into the community, and most are ending up on disability because of their stay in this facility. The public need to be aware of where their tax dollars ain’t going.”

Machelle Pearson, another former WHVCF inmate, was the first 17-year-old to be sentenced to life without parole in the prison. She served 34 and a half years, and she says she still struggles with outbreaks of mold on her skin, scarring, and other health conditions caused by the mold exposure.

“It’s horrible in there, and being a child going in there is beyond inhumane,” she says.

Pearson says she knew Clark before she was incarcerated, and the changes in her are stark.

“To see her like she is now is heartbreaking. I met her kids and held her son as he broke down in my arms. I know the pain her family is enduring,” Pearson says.

Clark’s supporters allege that she has also faced retaliation by prison staff for speaking out against conditions. Due to the mold in her lungs, she has breathing problems and uses a walker to get around. She used to be able to keep a rescue inhaler in her cell but now has to use her walker to walk down the hall and ask staff for it during meal times. Duckworth says this essentially forces Clark to choose between medication and food.

Pearson says MDOC has been able to stave off criticism and the need for mold remediation by moving inmates around to facilities including converted offices, storage spaces, and TV rooms while WHVCF was supposedly “under renovation.”

“They transferred us [so many] different places, only to put us back there,” Pearson says. “They said it was under construction, but it was a lie.”

Audrey Hutchinson spent three and a half years at the women’s prison and says breathing in mold contributed directly to her diagnosis of emphysema at age 37.

“I know it’s from the mold, but I don’t know how many years it took off my life,” she says. “I did my crime, and I did my time, but I did not deserve the life sentence I got from the negligence of the state to protect us. We know what we did and why we’re there, but that doesn’t mean we deserve to live in a death trap.”

Advocates are also concerned about the health of WHVCF guards and other staff, who are mostly women.

“You have a right to work in a mold-free environment,” Duckworth says.

In an emailed statement, Jenni Riehle, public information officer for MDOC, said: “The Michigan Department of Corrections is committed to the health and safety of those under our supervision and those employed by the department. Routine inspections of all MDOC facilities regularly take place. In the event that dangerous or hazardous conditions are found, they are addressed in a timely manner. We take the health care of incarcerated individuals very seriously and provide a consistent community standard of care which includes access to onsite medical staff, outside specialists when needed, and quality medications and medical equipment.”

In response to questions about mold remediation at WHVCF, Clark’s condition, and Trevino’s medical neglect allegation, Riehle emailed: “Due to health privacy laws, MDOC cannot provide information on the health or medical condition of any specific person without their written consent. In addition, due to active litigation, the department declines to provide additional comment on allegations brought forth on Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility and all parties listed in that lawsuit.”

Duckworth says she thinks remediating mold at WHVCF should receive bipartisan support.

“To me, this is a failure of our Democratic government. Gretchen Whitmer has known since 2020 about this. Other folks have known longer,” Duckworth says.

Some legislators have gone to the MDOC’s ombudsman only to be told “everything is fine,” she says.

Legislators in the Oct. 17 “Survivors of the Valley” virtual meeting included Michigan Sen. Jeff Irwin and Michigan Rep. Reggie Miller. Irwin says he is “incredibly frustrated” at the lack of movement on the issue. He says his staff have been working on getting independent observers into the prison. Miller says “the women of Huron Valley came there to serve time and not to come out with permanent health problems.”

“Our tax dollars are supposed to be taking care of these people,” Duckworth says. “On the MDOC website, it talks about their adequate health care, but that’s not adequate health care.”

Duckworth says anyone who would like to contribute to Survivors Speak’s effort can follow Survivors Speak’s social media and website, which includes a toolkit for those looking to hold MDOC and state government accountable for conditions in the prison. Survivors Speak is also organizing a “Stand Up, Speak Out” rally against MDOC at the Capitol building in Lansing from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Nov. 12.