Actors and puppets depict the end of the world in Belgian performance coming to Ann Arbor

“Dimanche” uses puppetry, mime, video, and multiple kinds of theater to tell the everyday story of the end of the world.

This story is part of a series about arts and culture in Washtenaw County. It is made possible by the Ann Arbor Art Center, Destination Ann Arbor, Larry and Lucie Nisson, the University of Michigan Arts Initiative, and the University Musical Society.

The inspiration for “Dimanche,” an indefinable performance that blends puppetry, mime, video, and multiple kinds of theater, began with a panel from Bill Watterson’s “Calvin and Hobbes” comic strip, according to Sandrine Heyraud-Danailov, one of the show’s creators.

“It’s not denial,” Calvin says in the panel. “I’m just very selective about the reality I accept.”

“Dimanche” aims to tell the everyday story of the end of the world. Its title (French for “Sunday”) is meant to imply something “very casual — where we’re having breakfast and we don’t want [the] apocalypse to arrive,” Heyraud-Danailov says.

The University Musical Society (UMS) will present the performance, a collaboration between Belgian companies Focus and Chaliwaté, Jan. 7-11 at the Power Center, 121 Fletcher St. in Ann Arbor.

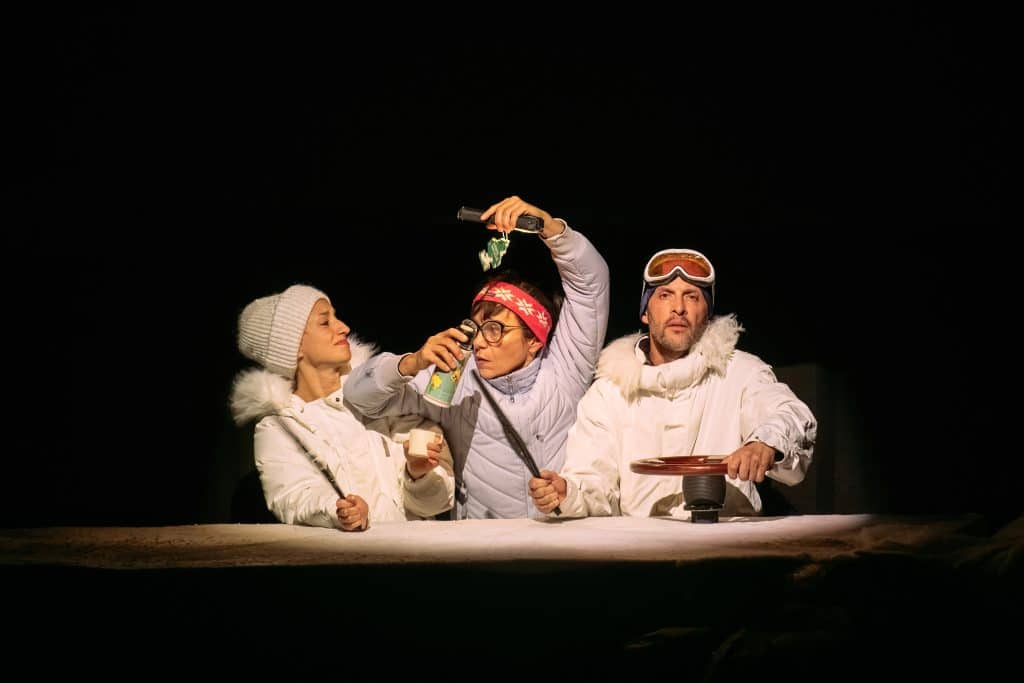

Set in the not-so-distant future, “Dimanche” tells two parallel tales. In one, a family gathers to spend their Sunday together as storms rage outside, trying — with increasing absurdity — to maintain a semblance of normality. In the other, a trio of wildlife journalists attempts to report on the world’s annihilation, using very little equipment, as they film three wild animals facing imminent extinction.

Heyraud-Danailov, who is also one of three performers in “Dimanche,” says the performance explores “the gap between the need to act, facing climate change, and what we saw as our incapacity to translate this [need to act into] our daily routines and lives.”

In that sense, “Dimanche” is at least partly about the all-too-human need to continue maintaining our own delusions, even when that need conflicts — as it must — with the even more urgent need for action.

Heyraud-Danailov and her collaborators, Sicaire Durieux and Julie Tenret, began working on the performance, which ultimately took three years to complete, in 2016.

At that point, their concern was that the finished show would be “too moralistic,” Heyraud-Danailov says. They wanted to avoid a sanctimonious or didactic tone.

Instead, Heyraud-Danailov says the artists approached their topic with humor, “even if it is a tragedy,” since comedy can provide an “emotional distance” from even the most difficult topics.

The end result is a blend of puppetry, object theater, and physical theater. Heyraud-Danailov says she and her collaborators tend to avoid the word “mime,” which so many people associate with an old-fashioned, archaic form of art; they prefer “physical theater” or “gestural theater.”

Both Heyraud-Danailov and Durieux attended l’École Internationale de Mimodrame de Marcel Marceau in Paris, the school started by iconic mime Marcel Marceau. There, they learned different “movement styles” before ultimately developing their own physical “language,” Heyraud-Danailov says.

Tenret’s background is more in puppetry and object theater, so, Heyraud-Danailov says, “we really blended these — all our skills — at the service of the story we wanted to tell.”

(That, she adds, can be one key difference between dance theater and object theater: dance tends to emphasize “the expressivity of the body, but in our case, we really try to tell a story.”)

For “Dimanche”, Heyraud-Danailov, Durieux, and Tenret also worked with the renowned sculptor Ron Mueck, who is known for creating hyper-realistic puppets.

Mueck created animal puppets for the performance. Heyraud-Danailov says that while the realistic appearance of the puppets was certainly important, the specificity of their movements was absolutely crucial. She says she, Durieux, and Tenret wanted Mueck to find “the rhythm of [each] animal.”

“It was a long collaboration,” she says, with “a lot of going back and forth,” and they were thrilled with the end result.

Another major visual theme of “Dimanche” is what Heyraud-Danailov describes as a “game of scales.”

Many of the puppets, props, and other onstage visuals “activate our sense of proportions,” prompting the audience to “imagine how small we are facing nature,” Heyraud-Danailov says.

In the decade or so since “Dimanche” was first staged, “we see that there’s a lot less laughter [among audiences],” she adds.

And while Heyraud-Danailov has noticed an increased air of tension and fear around climate change both within the theater and without, she finds meaning in her work.

“We believe that [the] arts and being onstage — humor and poetry — it invites us to resistance,” she says.

Tickets and more information on “Dimanche” are available here.