American political dissent highlighted in new U-M Museum of Art show

In a new exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, curator Julie Ault examines “how artists … have registered their politics or social effect in their art.”

This story is part of a series about arts and culture in Washtenaw County. It is made possible by the Ann Arbor Art Center, Destination Ann Arbor, Larry and Lucie Nisson, the University of Michigan Arts Initiative, and the University Musical Society.

In an increasingly partisan nation, says MacArthur fellow, artist, and curator Julie Ault, it’s more important than ever to highlight moments of political dissent in American history to understand “how they resonate with our present.”

In a new exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA), Ault, in collaboration with the University of Michigan’s Joseph A. Labadie Collection, examines “how artists … have registered their politics or social effect in their art.”

The exhibition, “American Sampler: Activating the Archive,” opens Jan. 24 at UMMA, 525 S. State St. in Ann Arbor.

Ault says her focus is not whether artists are somehow ethically beholden to engage with the social questions of their time — or, as she puts it, “the idea that art should or shouldn’t do one thing or the other.” Instead, “American Sampler” examines how artists and activists have expressed political dissent, with a particular focus on social movements from the ’50s to the ‘70s.

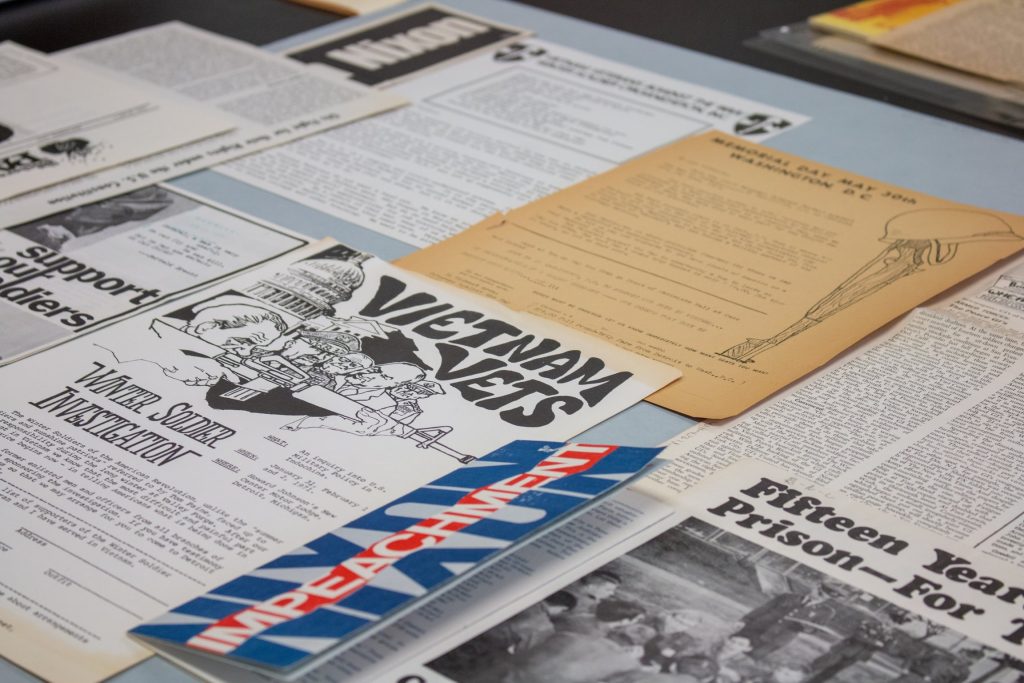

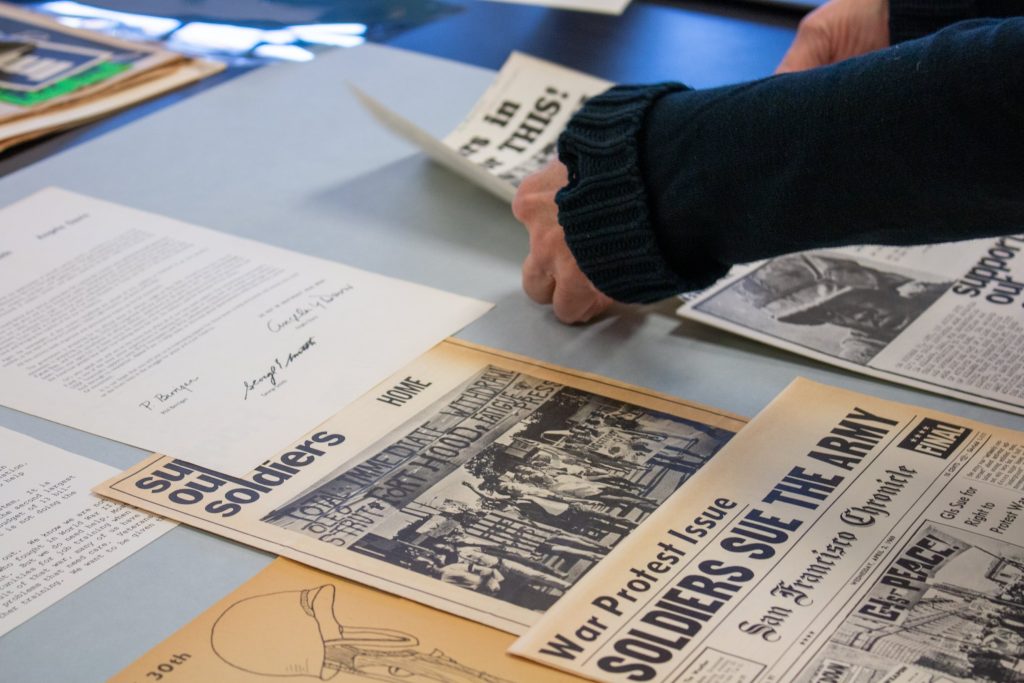

The exhibit includes “art and artifact and documentary materials” related to American opposition to intervention in the Vietnam War, the police riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, LGBTQ+ movements and anti-war Catholic radicals from the same era, and other political movements.

Ault was invited to curate a project drawing from the Labadie Collection, one of the country’s oldest and largest collections of anti-war, anti-colonialist, and anarchist materials, among other related subjects.

Ault, who describes the collection as “a fantastic treasure trove,” says she dove into the archive with no premeditated ideas about what kind of exhibition she’d ultimately like to curate. She says it was only after sorting through boxes of materials that she “figured out a path for what [she] was interested in bringing forward.”

“I was really interested in seeing some of the protests and the different collective [and] individual actions that were effective in confronting what many people thought at the time,” she says.

Some of that dissent “took place on a massive scale,” Ault says — such as the large civilian demonstrations and marches. At the same time, acts of dissent by individual soldiers or whistleblowers were also recorded.

Ault was also interested in the ongoing “simultaneity” of various civil rights movements: at the same time that anti-war protests were gaining momentum, for example, movements for Black power/liberation, women’s rights, and queer rights were all ramping up as well.

Ault wanted to know — and to show — how these various movements “intersected and fed each other” over the course of 10 to 15 years.

“The primary thing that I was interested in, and still am, is effective methods of dissent or protest,” she says.

Parts of the exhibition take a more literal approach to this topic: ‘70s-era Michigan Daily clippings about anti-war demonstrations, for example, are included. But other pieces “illustrate a certain open-endedness,” or “are more metaphorical” in their relation to the subject matter, Ault says — like Robert Indiana’s iconic 1967 “LOVE” silkscreen.

Over the course of the year, some of the materials in the exhibit will be switched out for others, meaning visitors may see new objects upon repeat visits.

“The exhibition remains alive, in a sense,” Ault says. “It’s not static.”

More importantly, she says, “the meaning that gets created – potentially – in the exhibition is from juxtaposition. We’re looking at things in relation to each other.”

In “American Sampler,” she says, Indiana’s “LOVE” gains meaning — and “takes on a particular depth” — not as an isolated, standalone piece of art, but from the context in which it’s been placed, the other works that surround it.

Ault says “there are a lot of layers” to the exhibition. She encourages visitors to approach and interact with the materials in their own way.

You might choose to walk through the exhibit and take a quick glance at the visuals, or you might read the more extensive captions Ault has presented in a small booklet that will be given away free.

“In some unfortunate ways,” Ault says, “this project ends up being more and more relevant daily.”

Now, she adds, “we are living the effects of different histories, including these histories.”

More information on “American Sampler” is available here.