Renowned Ann Arbor ceramicists’ sculpture garden to open to the public for free special event

John and Susanne Stephenson’s artistic legacy will be displayed in “The Complete Collection Unveiled,” a free special event Oct. 10-11.

This story is part of a series about arts and culture in Washtenaw County. It is made possible by the Ann Arbor Art Center, the Ann Arbor Summer Festival, Destination Ann Arbor, Larry and Lucie Nisson, and the University Musical Society.

Tucked into the trees off Waters Rd. in Ann Arbor is an unruffled, three-acre property where internationally renowned ceramics artists John and Susanne Stephenson made their home and studio for more than half a century — all the while “redefin[ing]” their field, in the words of their collections manager. Their artistic legacy will soon be made available to the public in a whole new way through a free special event Oct. 10-11 at the John and Susanne Stephenson Ceramic Sculpture Garden on their property.

John and Susanne Stephenson, who Collections Manager Patti Smith likes to refer to as the “dynamic duo of ceramics,” married in the early ’60s before moving into the Waters Rd. house. Susanne Stephenson’s sister, an architect, designed the house and studio. John Stephenson died in 2015 but Susanne Stephenson, who turned 90 this year, still lives on site.

Smith has spent the last few years working tirelessly to organize the couple’s archives, sell their remaining work, and — perhaps most importantly — cement their reputations as among the most notable ceramicists not only in the United States, but internationally. The Stephensons’ work has been shown at the Detroit Institute of Art; the Cranbrook Museum of Art in Bloomfield Hills; the Benaki Museum in Athens, Greece; and elsewhere. Individually, John Stephenson’s work has been exhibited in Korea and Germany. Susanne Stephenson’s has been shown in China; Denmark; the Victoria and Albert Museum of Art in London, England; and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, among many other museums and galleries.

More recently, Smith has also opened the Stephenson property to the public for guided tours, transformed the landscape into a sculpture garden, and opened a small gallery where their own work and that of guest artists is shown.

Smith estimates that the property drew a few hundred visitors in the summer of 2024, though this summer, she admits, those numbers have dwindled.

“We’ve had a real hard time getting people out,” she says.

In part to counteract that trend, the Stephenson sculpture garden will be transformed for a free event called “The Complete Collection Unveiled” on Oct. 10-11. Smith describes the event as a “festival of tents and tables,” intended to showcase a lifetime’s worth of work. In advance of the event, we stopped by for a guided tour of the sculpture garden.

Both John and Susanne Stephenson earned their Master of Fine Art degrees from the Cranbrook Academy of Art, where they studied with Finnish-American ceramicist Maija Grotell. Afterward, John Stephenson went on to teach at the University of Michigan (U-M), where he eventually received the Catherine B. Heller Distinguished Professorship Award.

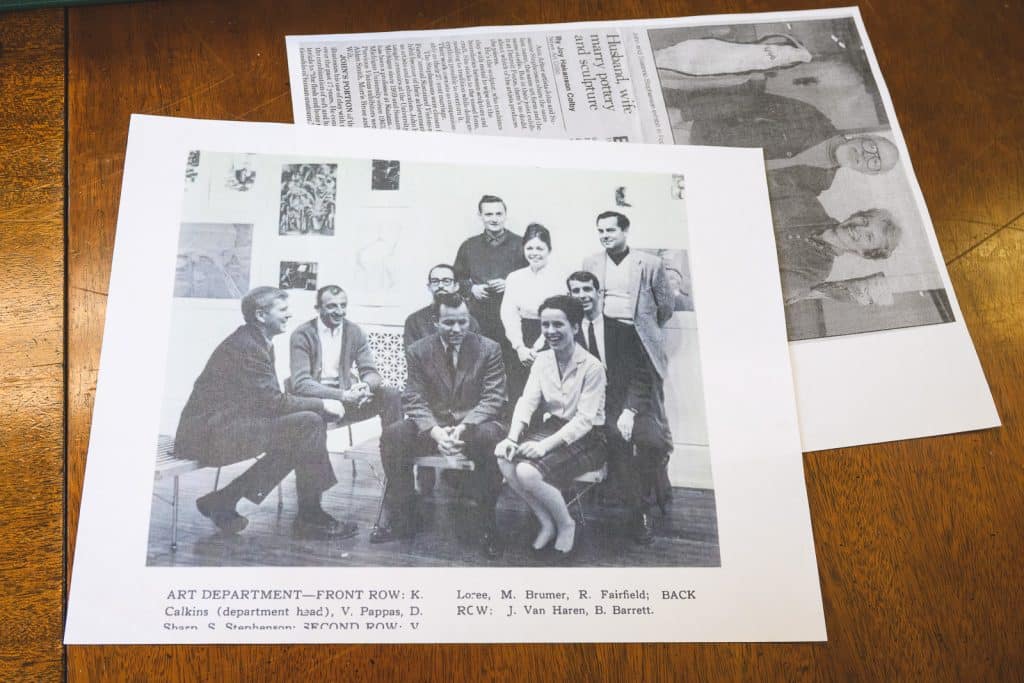

Susanne Stephenson was briefly hired by U-M, too, but after the couple were married, nepotism rules of the era decreed she had to work elsewhere, and Susanne Stephenson found a job at Eastern Michigan University (EMU). In 1963, she was one of only two women teaching in EMU’s art department, where she stayed for the next three decades.

In 1962, the Stephensons traveled to Shigaraki, Japan, to study wood firing and glazing techniques. The trip proved to be of seminal importance to both artists, and Smith credits it as the source of a major shift in both John and Susanne Stephenson’s work.

After they returned, John Stephenson’s use of mixed materials both increased and intensified: clay and metal began to appear together in his sculptures “in groundbreaking ways,” according to Smith.

Meanwhile, Susanne Stephenson’s use of the pottery wheel became far more confident and free — so much so that she was intrinsically “challenging the limitations of the [wheel’s] central axis,” Smith says.

John and Susanne Stephenson both experimented across materials and forms at various points in time. But according to Smith, once Susanne Stephenson reached the world of ceramics, she mostly stuck to it.

Susanne Stephenson actually began her career as a painter. In that role, Smith says Susanne Stephenson “wasn’t satisfied with the canvas because she couldn’t [achieve] the depth and the sculptural aspects of what she was trying to paint.”

(Susanne Stephenson has since destroyed all her early paintings because, according to Smith, “she didn’t like them.”)

Meanwhile, John Stephenson became increasingly interested in working in metal and Corten steel, particularly in the ’70s, when he created a number of large-scale sculptures now located on the Stephenson property.

According to Smith, John Stephenson maintained his own particular work processes, working on a series of pieces united in some way by material, color, or theme, until — in his own mind — he’d had enough.

“He’d create a body of work, and he’d complete his thought or his process, and he’d move on to something new,” Smith says.

What’s especially remarkable about that process is how he seemed to escape the pitfalls of the “jack of all trades, master of none” trap: in John Stephenson’s work, “every series is recognized with distinction,” Smith adds.

For one series, for example, John Stephenson had obtained a set of Vietnam-era photographic plates from the Ann Arbor News, which he used to make impressions and then sculptures. The series was immensely successful, Smith says, and if he’d wanted to, he could have chosen to make more of the sculptures.

But Smith says if “somebody asked [John Stephenson] to do more, he said, ‘No, thank you. I’m done with that series and I’m moving on.’”

According to Smith, neither John nor Susanne Stephenson wanted “to be part of the commercial [art] world.”

“That’s how much integrity they had,” she says. “They did not care.”

Laughing, she offers the following anecdote to illustrate her point:

John Stephenson was manning a booth at the Ann Arbor Art Fair when Smith says a patron “looked at one of his pieces and … said, ‘Boy … that’d make a great lampshade.’”

According to Smith, John Stephenson’s son-in-law was there to see him “fume up” and “turn red” but all he told the patron — “kindly,” Smith says — was, “I do not do lampshades.”

“This is what’s so unique and remarkable about [the Stephensons],” Smith insists. “They were so strong in their vision that all the chaos and criticism … didn’t waver them.”

The auger is a recurring image in much of John Stephenson’s work. Smith refers to it as his “iconic shape,” and describes him as an “engineer-head.”

According to Smith, it wasn’t just the shape of the auger itself that appealed to John Stephenson: “He was fascinated by the way dirt was moved after the auger had gone through. In some cases, he thinks of these [sculptures] as the product of what the auger left [behind],” she says.

(Smith also wonders if John Stephenson’s interest in the auger stemmed from the fact that he grew up in Iowa.)

For a period of time, Susanne Stephenson worked with porcelain, which Smith describes as a “nice blank canvas.”

But Susanne Stephenson grew frustrated with the material for a number of reasons. She was growing more and more interested in working on a larger scale, and porcelain, which shrinks during the heating process, eventually “falls apart; it’s very fine,” Smith says.

Meanwhile, she says Susanne Stephenson “wanted to keep working bigger … she just couldn’t work big enough.”

Then, too, Smith says Susanne Stephenson “couldn’t get the colors that she had in her mind”: the colors she eventually became known for producing in terracotta.

“They’re like tornadoes of color in the most beautiful sense. Her porcelain work is beautiful,” Smith adds, “but [it’s] quiet. … They’re somber [pieces]. They’re reflective of the sunsets out west, which [the Stephensons] traveled quite a bit.”

At a certain point, Smith says, Susanne Stephenson was “just done” with porcelain as a material: “She did what she could with porcelain and that’s all. She could move forward. She just didn’t want to explore it anymore.”

(“Good luck getting her to talk about the porcelain work,” adds. “She just won’t talk about it.”)

Asked to what extent she believes she influenced John Stephenson’s work, Susanne Stephenson says, “He worked with form more than I ever did, especially before we went to Shigaraki — more simplistic form and less painting.”

In Smith’s telling, Susanne Stephenson was careful — meticulous, even — not to allow any influence of John’s work to appear in her own. While it might have been natural for two talented artists in such close quarters to feed into each other’s work, as one of few women in ceramics at the time — and as the lesser-known name, then — Susanne had a reputation to build and protect on her own merit alone.

The Stephensons didn’t collaborate often; Smith doesn’t think they ever did.

“It’s hard to do,” Susanne Stephenson says, “so we didn’t really do many things that way.”

On the other hand, she adds, there was frequent, mutual “teamwork, which didn’t have to do aesthetically with making the piece, but just physically [maneuvering large objects around the studio].”

“You’ve got to know when to stop,” Susanne Stephenson says — to know when a piece is finished.

This was something she struggled with in her own practice. It got to the point that if she was working on a piece, she realized it was better to “do it during daylight.”

“Better that I do it when I have to get up and go somewhere,” with an externally enforced reason to stop, she says.

Near the end of our visit, Smith asks Susanne Stephenson, “Susie, how does it feel to be famous?”

Susanne Stephenson pauses.

“I don’t think I’m that famous,” she says.

“The Complete Collection Unveiled” will take place Oct. 10-11 from noon-4 p.m. at 4380 Waters Rd. in Ann Arbor. For more information on the event, click here.