Students respond to Ypsi history through art in “Ypsilanti Future History” project

Ypsilanti Community Schools students at all grade levels are learning about Ypsilanti’s history and making art about it in a project called Ypsilanti Future History.

On the Ground Ypsilanti is an “embedded journalism” program covering the city and township of Ypsilanti. It is supported by Ann Arbor SPARK, the Center for Health and Research Transformation, Destination Ann Arbor, Eastern Michigan University, Engage @ EMU, Washtenaw Community College, Washtenaw County Parks and Recreation Commission, and Washtenaw ISD.

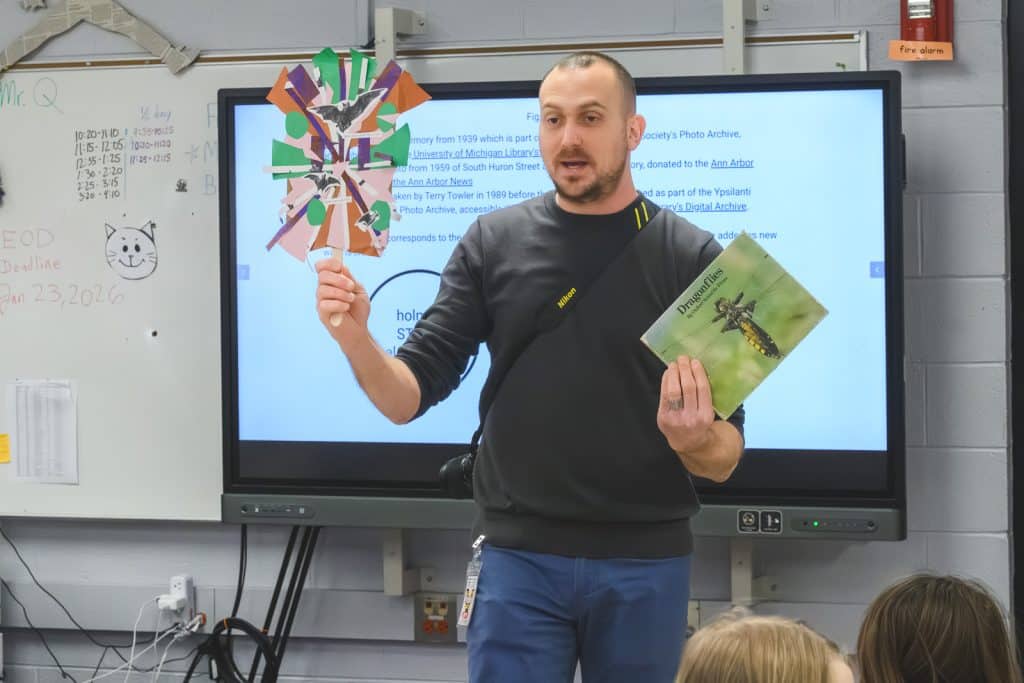

Ypsilanti Community Schools (YCS) students at all grade levels are learning about Ypsilanti’s history and making art about it in a project called Ypsilanti Future History. The program was funded by a Michigan Department of Education Section 99d Teaching Diverse Histories Grant and is headed by Ypsilanti artist Nick Azzaro.

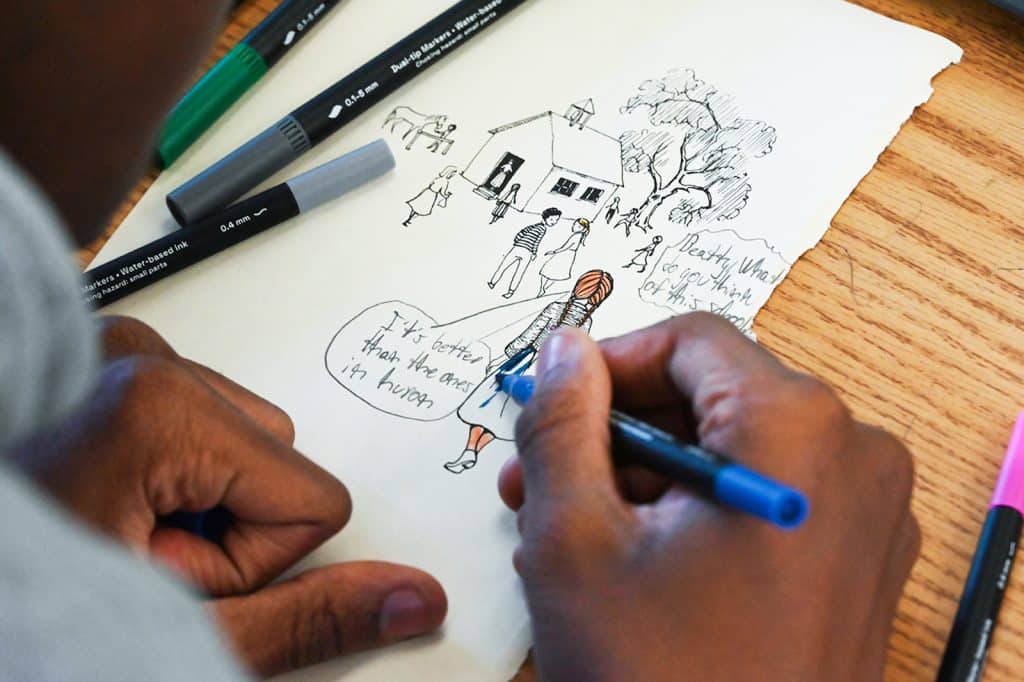

Azzaro is working in both art and social studies classes from elementary school to high school, helping students create artistic responses to prompts about Ypsilanti’s past and student hopes for the future.

Students work from prompts about influential people, events, and landmarks from Ypsilanti, from Ypsilanti lawyer Lyman Decatur Norris’ role in the landmark Dred Scott case to the city’s namesake, Demetrios Ypsilantis. This school year, students will examine a prompt relating to an incident when former Willow Run High School Principal Dr. R. Wiley Brownlee was tarred and feathered by the Ku Klux Klan for his inclusive and progressive views. They’ll also consider the importance of Ypsilanti’s milling industry, especially the Peninsular Paper Company, which supplied all the newsprint to the Chicago Tribune.

Azzaro developed the prompts in conjunction with YCS teachers, helping align the project with district-wide curriculum. The prompts encourage students to connect local events and politics with broader themes and to do their own independent study, he says.

Azzaro says his approach is to “make art as accessible as possible so that every student who wants to contribute has the ability.” He says he’s less concerned about teaching techniques than allowing students to follow their own creativity in responding to the prompts he gives them.

“The projects are meant to be open-ended,” he says.

Some projects take one day, while others take longer. Most can be done with any grade level, though a few can only be done with older students. In a lesson regarding urban renewal on Ypsilanti’s Southside, older students painted Faygo bottles and filmed the bottles being smashed (while students were safely separated from any shattering glass). These small films were meant to represent the destruction of the Faygo distribution center at Harriet and Huron, and other businesses that disappeared under the urban renewal plan of the ’60s.

When Azzaro was teaching students about the disastrous local effects of urban renewal, he heard frequently from parents that they remembered The Armory, an unofficial party venue that used to exist on the Southside near the current site of the Buffalo Wild Wings restaurant.

To honor that small piece of Ypsi history, a recent lesson revolved around The Armory. Students learned a little bit about the venue, the bands that were reputed to have played there, and the wild fashions people wore there. In response, students decorated simple paper masks with wooden handles, made with paint paddles. Azzaro says the simplicity is intentional. He wants students to be able to replicate most or all the projects at home with their own materials on hand, he says.

“My objective is to begin each class with a brief but concentrated lesson about a point in Ypsi’s history, and then give the students most of the time to create a response,” Azzaro says.

Erickson Elementary third grader Addy Boggs cut the edges of her mask into cat ears because she likes cats, she says. Another student says she colored ladybug wings on her mask because she likes ladybugs but also finds their splayed wings kind of creepy.

Another third grader, Damian Kamari-Williams, got creative and used what was intended as the back of the mask, incorporating some dark electrical tape into his design.

“On this side, it’s the inside of the robot, and on the other side, it’s the outside of a robot,” he says. “I like robots because they remind me of the Terminator.”

Erickson art teacher Heidi Roberts says her pupils have responded with excitement to the project.

“They’ve been really excited every time [Azzaro] comes, and really engaged, even kids that usually aren’t,” she says. “They’ve been really interested and always are asking to get their projects back because they’re excited about them.”

Many of the prompts require multiple weeks to complete, as was the case with the Armory assignment. Students responded to the lesson in the first session. The next week, Azzaro returned to set up a backdrop with lights and photograph each student with their mask.

Azzaro has also been recording classroom discussions and interviews, and says he’d love to partner with the high school’s podcasting program. The recordings will be combined with Azzaro’s photo documentation of students’ art and displayed in a show that will be open to the public. At that event, students will speak about the art-making process and what they learned.

See details about the lessons and student responses to the prompts at YpsiFutureHistory.com.